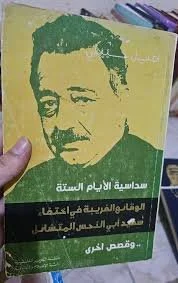

Emile Habibi was a giant of modern Arabic letters. Years ago, some students and I translated his post-1967 fiction, Sudasiyyat al-ayyam al-sitta. After watching our translation gather dust for the past eight years, I am pleased to present it to you here: The Six-Day Sextet. This is an open access translation—which means it is offered to you free of charge, for your personal use. Please read, print, distribute, and share as you like.

Muin Bseiso, “The Besieged City”

trans. Ahmed Saidam and Elliott Colla

To the stars, the Sea tells the tale of a captive homeland,

While, with tears and moans, Night knocks like a beggar

On the doors of Gaza, which are shut upon the grieving people.

It stirs the living who sleep upon the rubble of years,

As if they were a grave disturbed by graverobbing hands.

The morning light nearly shows from the weight of pain,

As it chases the Night, still youthful and strong

But now is not the hour of its coming or going

The mighty giant has covered its lofty head with dust,

Like the sea which is shrouded in fog, but not killed by it.

Dawn speaks to the city, confused and unanswering.

Before her lies the salty sea. Within her, barren sands.

While alongside her, the suspicious steps of the enemy.

What does Dawn say? Have the roads to the homeland opened?

So we may bid the desert farewell and walk toward the fertile valley?

To the wheat stalks that have ripened and await harvest:

Suddenly they are given to fire, to scattering birds, to locusts.

Night marches on them, dressing them in black on black.

And the river, rushing through mountain and valley,

He casts his staff down upon the ruins and turns to ash.

Here she is, Beautiful Gaza, as she wanders through her funerals,

Between the hungry in their tents and the thirsty in their graves.

And a tormented man, feeding on his own blood, squeezing roots for juice.

These are mere images of humiliation: My Captive People, you should rise in anger!

Their whips have written our fate across our backs.

Have you read about it—or are you still weeping over the lost homeland?

Fear has bound your arms, and so you flee from the struggle.

‘I have drowned,’ you say. ‘The wind has torn my sail!’

O you, wretched in an earth roaring with light:

Sing the songs of struggle, and join the long march of the hungry!

Source: Mu‘īn Bisaysū, Al-Aʿmāl al-shiʿrīya al-kāmila (Beirut: Dār al-ʿAwda, 2008), 42.

"المدينة المحاصرة"

للشاعر معين بسيسو

البحر يحكي للنجوم حكاية الوطن السجين

والّليل كالشحّاذ يطرق بالدموع وبالأنين

أبواب غزة وهي مغلقة على الشعب الحزين

فيحرّك الأحياء ناموا فوق أنقاض السنين

وكأنّهم قبر تدقّ عليه أيدي النابشين

وتكاد أنوار الصباح تطلّ من فرط العذاب

وتطارد الّليل الذي ما زال موفور الشباب

لكّنه ما حان موعدها وما حان الذهاب

المارد الجبّار غطّى رأسه العالي التراب

كالبحر غطّاه الضباب وليس يقتله الضباب

ويخاطب الفجر المدينة وهي حيرى لا تجيب

قدّامها البحر الأجاج وملؤها الرمل الجديب

وعلى جوانبها تدبّ خطى العد، المستربب

ماذا يقول الفجر هل فتحت إلى الوطن الدروب

فنوّدع الصحراء حين نسير للوادي الخصيب ؟

لسنابل القمح التي نضّجت وتنتظر الحصاد

فإذا بها للنّار والطير المشرّد والجراد

ومشى إليها الليل يلبسها السواد على السواد

والنّهر وهو السائح العدّاء في جبل وواد

ألقى عصاه على الخرائب واستحال إلى رماد

هذي هي الحسناء غزة في مآتمها تدور

ما بين جوعى في الخيام وبين عطشى في القبور

ومعذّب يقتات من دمه ويعتصر الجذور

صور من الإذلال فاغضب أيها الشعب الأسير

فسياطهم كتبت مصائرنا على تلك الظهور

أقرأت أم ما زلت بكّاء على الوطن المضاع ؟

الخوف كبّل ساعديك فرحت تجتنب الصراع

وتقول إنّي قد غرقت وشقّت الريح الشراع

يا أيّها المدحور في أرض يضجّ بها الشعاع

أنشد أناشيد الكفاح وسرّ بقافلة الجياع

al-Tha‘alabi: Types of Loud Noises

Types of Loud Noises

Any forceful voice is al-ṣiyāḥ (to shout, cry). Al-Ṣurākh (and al-ṣarkha) is the sharp cry that comes from fright or calamity. Close to it in meaning is al-za‘qa (shriek) and al-ṣalqa (grating cry, especially during battle). Al-Ṣakhb is the noise made during argument and quarrel.

Al-‘Ajj is the raising of the voice when one says the ritual phrase, “Here I am to serve you!” or when one invokes the name of God during slaughter. Al-Tahlīl is to raise one’s voice in saying, “There is no god but God and Muhammad is the Prophet of God.” Al-Istihlāl is the first cry of the newborn child.

Al-Zajal is to raise the voice when one is moved by music. Al-Naq‘ is the loud scream. Al-Hay‘a is the cry of fright, as in the Prophetic tradition: “The best of men is the one who holds fast the reins of his steed and the one who, when he hears the shriek of fear, flies toward it.” Al-Wā‘īya is the crying lament over the dead. Al-Na‘īr is the shouting of the victor over the vanquished.

Al-Na‘īq is the sound of the shepherd calling his flock. Al-Hadīd (and al-hadda) is the fierce noise you hear when part of a building or mountain collapses. Al-Fadīd is the farmer's throaty call to oxen or donkeys while working in the field. As mentioned in the Prophetic tradition, “Brusqueness and harshness are traits of the loud-voiced men in the field.”

Al-Ṣadīd (to laugh out loud, to raise a clamor) is another loud noise, as is al-ḍajīj (to raise a tumult), and appears in the Qur’an: When Mary’s son was given as an example, your people howled with laughter (Surat al-Zukhruf: 57), which is to say: they raised a clamor, a tumult, a ruckus. Al-Jarāhīya is the sound of people when their words are spoken publicly and openly rather than in secret and, according to Abu Zayd, is similar to al-hayḍala (the hue and cry of battle).

Fiqh al-lugha wa-asrār al-‘arabīya, ed. Yāsīn al-Ayūbī (Saydā’: al-Maktaba al-‘Usrīya, 2008), 238-9

al-Tha‘alabi: Types of Sleep

The prolific anthologist ‘Abd al-Mansūr ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Muhammad al-Tha‘alabi (961-1038) was the author of the encyclopedic lexicon, Fiqh al-lugha wa-asrār al-‘arabīya (Fundamentals of Language and the Secrets of Arabic). In this original work, al-Tha‘alabi organizes vocabulary according to remarkably subtle distinctions.

To honor the long nights of the present season, let us begin with sleep.

Types of Sleep

The first stage of sleep is al-nu‘ās (drowsiness), which is when a person needs to sleep. Then comes al-wasan (nodding off), which is when the drowsiness becomes heavy. Then comes al-tarnīq (dimming), which is when the drowsiness makes the eyes begin to shut. Then come al-kurā and al-ghumḍ, which is when a person is between sleeping and waking. Then comes al-taghfīq, which is the kind of sleep when you hear people talking (this by way of al-Aṣma‘ī). Then comes al-ighfā’, which is light rest. Then comes al-tahwīn, al-ghirār and al-tahjā‘, which is a short kind of sleep. Then al-ruqād, which is a long sleep. Then al-hujūd, al-hujū‘, and al-hubū‘, which are forms of deep slumber. Finally there is al-tasbīkh, the soundest form of slumber.

— Fiqh al-lugha wa-asrār al-‘arabīya, ed. Yāsīn al-Ayūbī (Saydā’: al-Maktaba al-‘Usrīya, 2008), p. 205.